Yet another tragedy

01/07/13 05:18

One of the stories that was part of the culture and known to me was the story of the Mann Gulch tragedy. It happened before I was born, but I knew the story. It was August of 1949. A crew of fifteen elite smokejumpers were flown to the Mann Gulch area in the Helena National Forest on a C-47 operated by Johnson Flying service. The drop was nearly perfect. They parachuted into the drop zone and their equipment was also dropped. Spotters saw them retrieve their equipment and head toward the blaze. Shortly afterward, a dozen of them were dead. They were burned by the fire while trying to escape the flames in a desperate uphill race. The general opinion of the people who told the story to me was that they never had a chance. You can’t outrun a fire burning up hill.

That was after I had failed the eyesight test for becoming a smokejumper, after I had made the decision not to go into the family flying business, after I knew that my life would not be centered around western wildfires. The closest I had ever come to a fire line in my life was fighting fire in wheat stubble with wet gunny sacks where the flames rarely rise above your head and it is obvious that you can run through the flames if necessary to avoid serious injury.

But my heart catches when I read of the loss of firefighters.

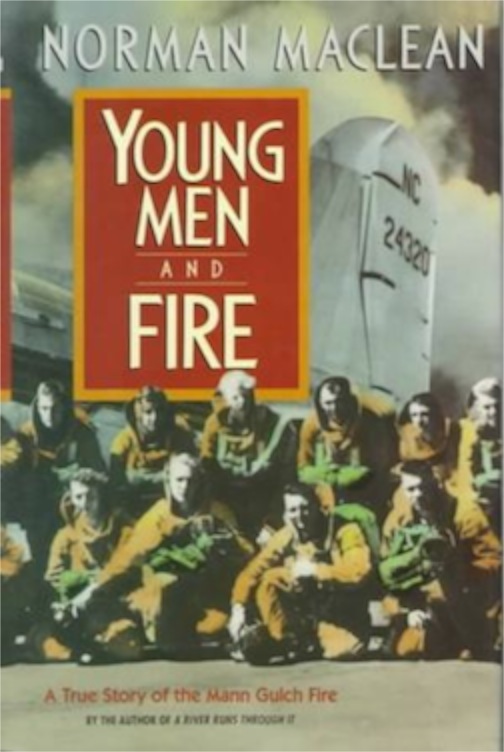

Part of me doesn’t want the details. I want to respect the families who have experienced this awful tragedy. I want to respect the Arizona firefighting community who have to be reeling with the news. I don’t like staring grief in the face. I hate it when television camera operators don’t have the good sense to turn their cameras off. I am afraid that someone will obsess with the details of the tragedy like Norman Maclean did in his book and that there will be far more information available than I want to know.

And I know that I will read every article about the fire that I can find. Despite my aversion to the gory details, I too am obsessed with firefighting tragedies. I keep hoping that we will learn enough to save lives. And we have learned a lot. Crews have much better fire shelters with them than they used to carry. They are better trained. They have better tools for knowing where they are and where the fire is headed. And the tragedies are a bit fewer and farther between.

Fighting wildfire, however, is still very dangerous. A fire shelter gives you about a 50/50 chance of survival once it is deployed. Firs behavior is unpredictable. Exhaustion and dehydration are real dangers that affect judgment and decision making. And it is hot in Arizona. Temperatures away from the fire are exceeding 120 degrees.

This is a nasty fire. One source reported that about half the homes in Yarnel have been destroyed. But homes can be replaced. The property that is lost can be recovered or replaced. People cannot.

So Yarnell will be added to the list of infamy. Blackwater in Wyoming, Mann Gulch in Montana, Rattlesnake in California, Storm King Mountain in Colorado, and now Yarnel. They are all places where heroes have fallen. They are all lessons in how vulnerable lives are and how risky fighting fire can be. And so we study the tragedies to learn what we can to prevent the next one.

No matter how painful it is to examine the story, it must be done. It is clear that we haven’t learned enough yet.

For now we pray for the families who also have become victims of the fire.