The things we do not know

28/02/13 05:33

A couple of items from the science news caught my attention recently. One was a TED talk in California yesterday by Stuart Firestein, chair of the biological sciences department at Columbia University. Firestein said that science has been put on a pedestal and that scientists have been rebranded as “fact producers.” He seems to be right when you listen to popular media. Too often a small amount of the work of a particular scientist is quoted in the media to support a political position or to “prove” a point. The debate over the proposed construction of the Keystone XL pipeline is an excellent example. Those on both sides of the argument find snippets of information from scientific studies, call those bits of information “facts” and use them to support their point of view. A student of logic could easily point out the fallacy of such arguments, but public debate is rarely couched in the rules of logic. In my experience the average high school debater is far more likely to present a logical argument than a legislator. And the television news is even less logical than the debate in the legislature, if such a thing is possible.

At any rate, the thing that was inspirational about Mr. Firestein’s talk was his urging that ignorance should be celebrated. It is, after all, the job of science to analyze the gaps in knowledge – to be brutally frank about what we don’t know. It isn’t a collection of facts that makes a scientist – it is the understanding of what remains unknown. Science isn’t a puzzle that needs to be put together to be complete, he explained. There is no puzzle and most science is never complete.

George Bernard Shaw is famous for his quote, “He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.” But in fact, Shaw was a man who both could and who taught. And he had a lot more to contribute to the philosophy of science. He also wrote, “Science becomes dangerous only when it imagines that it has reached its goal.” A truly educated person comprehends that we have very little knowledge when compared with the vast amount of things that we do not know. Science ought to be about at least understanding that the majority of the universe is unknown. The Irish playwright also penned, “Science is always wrong. It never solves a problem without creating 10 more.” That could be interpreted as a condemnation of science, but in reality it is a celebration. There is so much more to understand than we can comprehend that a truly educated person realizes that life is a continual discovery of the unknown. What we don’t understand is far more vast than what we are capable of knowng.

To treat science as a producer of facts is to demean a much bigger and grander pursuit. Mr. Firestein said, in his talk, that “we commonly think that we begin with ignorance and we gain knowledge.” He continued, “The more critical step in the process is the reverse of that.”

Answers create questions and the true scientist dives into the questions, not the answers. In order for us to continue to produce new generations of scientists, we need to cultivate a love of the unknown and the unanswered. To get excited about science we must focus on what we don’t know rather than on some perceived accumulation of facts.

It is a tragedy that we are raising a generation of young minds who think that all of the answers are “out there.” They search the Internet on their smart phones and think that all they have to do is to find the answer that satisfies them in the vast universe of data that already exists. Such a pursuit is a fool’s errand. The true challenge is found in embracing mystery. When students focus on accumulating facts, they ignore the areas where ignorance exists and where there are answers yet to be solved.

The joy of life doesn’t lie in the facts. It lies in the pursuit of truth in the midst of ignorance. We can’t discover that joy until we become aware of the ignorance.

This is true in theology as well as in the other sciences. The claim that we know and understand God is simply another way of admitting that our vision of God is far less than the reality. God is much grander and more complex than we are capable of understanding. When we admit that there is much that we don’t know and can’t understand, the joy of the relationship with God expands and theology becomes a task worthy of a lifetime and beyond.

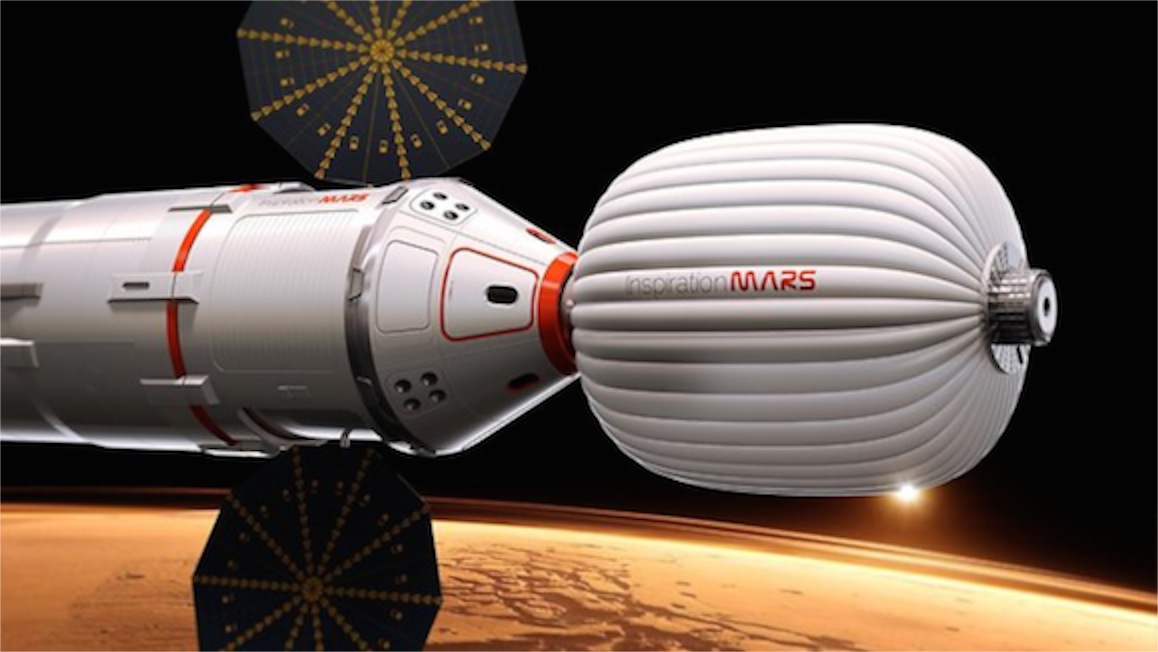

I was also interested in the story that multi-millionaire Denis Tito, the first space tourist, who reportedly paid 14 million British pounds to spend six days on the International Space Station in 2001, is now funding a private expedition to Mars. The team planning the expedition announced yesterday that it is looking for a “tested couple” in their 40’s or 50’s to take part in a 16-month mission to Mars. Explaining that they were worried about the stress of living in a confined space for such a long time, the planners of the mission have focused their search on couples that have been through stress and seen their relationship strengthen and grow.

According to chief technical officer Taber MacCallum, the actual flight could happen within the next five years. The couple would get within 100 miles of Mars, but would not perform a space walk. That means 16 months living aboard a tiny spacecraft, with minimal food, water and clothing. It won’t be an easy mission.

My reaction was “right on!” I think that couples who have been married for a long time have skills at living together that are valuable. I think that the ability to live together in a cramped space is a skill that takes a lot of practice. Susan and I have lived for up to a month and a little more in our pickup camper. It has exactly 2 feet by 6 feet of total floor. If one person is standing up, the other either has to be in bed, in the dinette or in the bathroom. We do quite well in that space.

But, alas, we are too old for the project. Then again, they won’t find any couples in their 40’s who have been happily married for 40 years. Maybe we should apply just on the odd chance that experience sometimes is worth more than youth. At least we can admit that there is a lot we don’t know.