A Real Dictionary

01/02/13 05:24

I started my day with a tiny computer glitch that struck me as delightful. The History Channel has a web site that shows a brief video and provides a bit of text called “This Day in History.” It usually highlights a few things that happened on the particular day and chooses one story for just a little bit more detail. Since I have been watching for several years, now and since the cays repeat every year, I do know that sometimes they choose a different story from the previous year, sometimes they repeat that story.

At any rate, today I went to the site and the video is not playing. Instead of the usual video, there is just a black screen with an ad on the left. I refreshed the screen. I reloaded my browser – always the same effect. I concluded that the problem must be with the site. Someone made a mistake on the upload. They will discover the problem and the video will be running soon enough. I read the text portion of the site and went on with my day.

Then I got to thinking what fun it was to have the video not working. The topic today is perfect for a video that can’t tell the story. On February 1, 1884, the first portion of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was published. I am a huge fan of the OED, though I never have owned a copy. No worries, technology now makes the OED accessible to me without a trip to the library because its online resources are fantastic. The OED is considered by many to be the most comprehensive and accurate dictionary of the English language. There are some who believe that all dictionaries are the same. They probably also don’t know that dictionaries contain errors and that you can get incorrect information from dictionaries. They may also be unaware of the rapid pace at which our language evolves and how rapidly meanings change.

That rapid pace of change proved to be a huge challenge for the original writers and editors of the OED. Members of the London Philological Society were frustrated with how rapidly dictionaries became out-of-date. They were also frustrated with errors contained in the available dictionaries. They decided to produce one that would cover all vocabulary from the Anglo-Saxon period (about 1150 AD) to the present. Mind you this was in 1857, when the English Language had a vastly smaller vocabulary than is the case today. Still the task was daunting – and much bigger than the originators imagined.

They believed that a 4-volume, 6,400 page work would cover the language and that it could be completed in 10 years. The estimate was significantly shy of the reality. It took over 40 years until the final fascicle (portion) of the dictionary was completed in April of 1928. The work came in at over 400,000 words and phrases in 10 volumes.

What makes the OED so much fun for those of us who love language is that the OED gives a chronological history of the use of each word and phrase, citing quotations from famous sources. The quotations line up as a sort of history of literature. I have ended up reading books that I might not have otherwise read because of the quotes I discovered in the OED.

Here is a fantasy that only a bibliophile could have: wouldn’t it be a hoot to write something that got quoted in the OED? Instead of just scrambling and jumbling word order, which is the kind of writing I do, some people actually contribute to the shaping of the language and the understanding of its meaning. Don’t look for a quote from me in the OED anytime soon.

But then that last bit of advice is not good advice. If you want to look at the OED, the time to start is as soon as possible. I read a lot. I’m guessing that at my current rate of reading it would take more than 150 years for me to read the OED if I made it the only thing that I read. There is more than a lifetime in that set of books.

In the mid-1980’s the OED came out with a 4-volume supplement with words, phrases and meanings from North America, Australia, the Caribbean, New Zealand, South Africa and South Asia. After all there are more people who speak English in India than in the United States. The same is true of China.

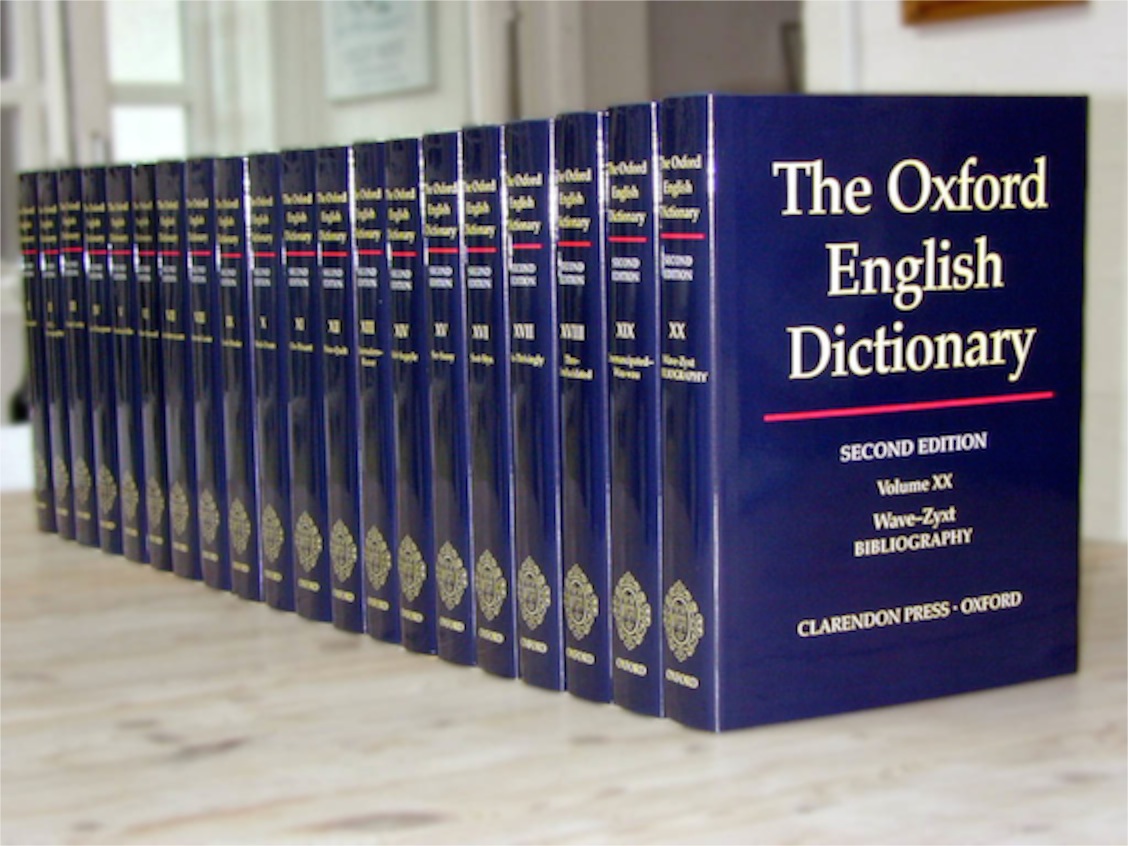

The second edition of the OED is available online. It now has topped 20 volumes. The print version weighs 137 pounds and contains 59 million words. At 215 British Pounds (about $340 at the current conversion rate) the price of a one-year subscription to the OED is beyond my comfort level, so I won’t be subscribing. Institutions can get a free 30-day trial, and I have been tempted to register the church library for the free 30 days, but in the end I think that is not really fair because I know we have no intention of subscribing. The University of Wyoming has a subscription and I’ve browsed through the OED online.

It is possible to purchase the actual books. The hardcover edition comes in at 20 volumes, 22,000 pages and costs $995.00. On the other hand, it is likely I’ll spend more than $995 over the course of my lifetime on other books. I might tire of only reading the dictionary, even with the substantive and pithy quotes. Also one wouldn’t quite know where to begin. If you start at the beginning, you become expert in only the start of the alphabet because life is too short to read the entire thing. Perhaps you switch volumes every month to get a more broad based approach.

Since the OED is now updated quarterly with more than 1,000 new and revised entries each quarter, it is likely that just keeping up with the changes is to large of a task for an individual.

So if you have a sense of humor like mine, you might find it amusing that even the History Channel couldn’t capture the OED with a video clip. There is just too much there to put into a video. Besides, if you want to know the OED, the way to do so is by reading and not watching video. In the flow of life, I find reading to be more satisfying than video anyway.