Hauling Logs

21/03/12 05:25

The town I was raised is named Big Timber. The name does not come from having particularly big trees. There are some old cottonwoods around, but that it is about all. Here’s how the name came to be. On their Eastward return from the Pacific Coast, Lewis and Clark divided their expedition near the headwaters of the Missouri River. Lewis and his crew followed the Missouri and spent some time exploring the Marias. Clark and crew hiked over the Bozeman pass and found the Yellowstone River near the present-day town of Livingston. By the time they got to the confluence with the Boulder River they had been walking for a little over 60 miles. There they finally found trees that were big enough to carve dougout boats so that they could begin river travel. The boats meant that the remainder of the trip would be less strenuous. They named the place where the found the trees Big Timber.

I spent an additional ten years of my life in Boise, Idaho. The story of that town’s name dates back to the days of French Fur trappers who were said to have uttered upon discovering the area, “Les Bois!, Lest Bois!” Actually the trees in Boise aren’t all that spectacular. It seems that the fur trappers had been wandering in the desert for several days and so just finding a place with some trees was an exciting discovery.

Still, I have had a deep appreciation for trees all of my life. All of my growing up summers included time at our Church Camp, Mimanagish, high up the boulder valley nestled in huge stands of lodgepole pine. There really is something very wonderful about the whisper of the wind in the pine trees. I assumed that I would always live in a place where there was an ample supply of trees.

Graduating from seminary, however, we found ourselves called to rural North Dakota. I had a fairly large collection of North Dakota jokes and some biases about life on the prairie. I had tried to find a call in a mountainous location, but God has a wonderful sense of humor and we headed across the prairie to our new home. My biases turned out to be wrong. It was a wonderful place to live. I grew to enjoy the open space, the ability to see long distances, the view from the top of a small hill or rise, and especially the people who lived there. To be honest, our town was not without trees. There just weren’t very many of them outside of town.

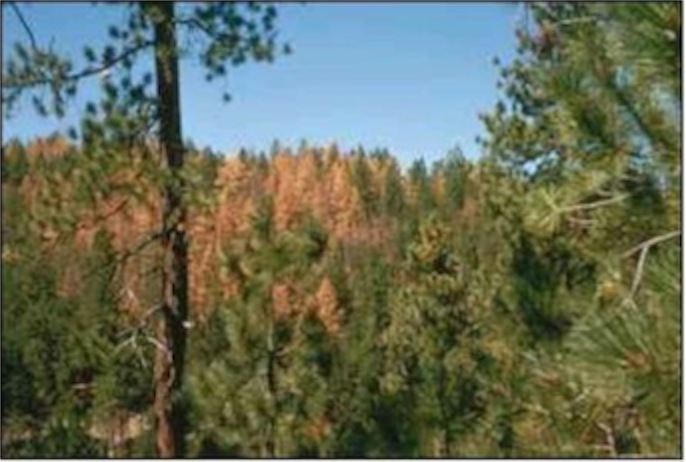

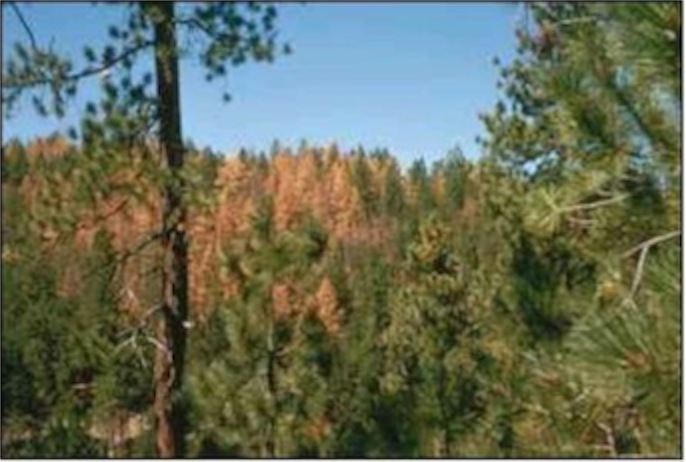

When the time came for us to move to the Black Hills, we were delighted to find our home at the edge of the hills with pine trees all around. There are a few spruce in the hills, a smattering of birch, some clusters of oak and aspen and cottonwoods, but the primary tree of the Black Hills is the Ponderosa Pine. Old photographs from the time of the Custer expedition show far fewer trees in the hills than we have these days, so we know that periodically over the years, fires and insects have taken their toll on the trees in the hills. Still, knowing it doesn’t make it any easier to accept the attack of pine bark beetles that have been decimating our forest for the past few years. It is not something restricted to the Black Hills. All across the west millions of acres of pine trees are dying from the infestation. The tiny critters seem to find more trees to attack and multiply at faster rates during periods of drought and stress on the trees and the long northwest drought a decade ago gave them a real start in many areas. Across the west, we have grown used to seeing a tri-colored forest. There are green trees, many of which are already infected by the beetles, red trees, with needles still attached but clearly dead and grey trees, from which the needles have fallen. The dead and dying trees are especially vulnerable to fire and when huge stands of trees are affected, fires spread more quickly and grow much bigger. It all may be part of the cycle of nature, but it sure changes the vista for the folks who live in the forest.

When the time came for us to move to the Black Hills, we were delighted to find our home at the edge of the hills with pine trees all around. There are a few spruce in the hills, a smattering of birch, some clusters of oak and aspen and cottonwoods, but the primary tree of the Black Hills is the Ponderosa Pine. Old photographs from the time of the Custer expedition show far fewer trees in the hills than we have these days, so we know that periodically over the years, fires and insects have taken their toll on the trees in the hills. Still, knowing it doesn’t make it any easier to accept the attack of pine bark beetles that have been decimating our forest for the past few years. It is not something restricted to the Black Hills. All across the west millions of acres of pine trees are dying from the infestation. The tiny critters seem to find more trees to attack and multiply at faster rates during periods of drought and stress on the trees and the long northwest drought a decade ago gave them a real start in many areas. Across the west, we have grown used to seeing a tri-colored forest. There are green trees, many of which are already infected by the beetles, red trees, with needles still attached but clearly dead and grey trees, from which the needles have fallen. The dead and dying trees are especially vulnerable to fire and when huge stands of trees are affected, fires spread more quickly and grow much bigger. It all may be part of the cycle of nature, but it sure changes the vista for the folks who live in the forest.

We hate to lose any tree. Losing thousands is no picnic.

One of the ways to slow the spread of the beetles is to remove the affected trees. Many landowners have been aggressive about felling trees lost to the beetles. The trees are then cut into short lengths and left scattered in the forest. Another technique is to cover the loges with plastic to contain the insects and raise temperature levels. An even better technique is to haul the logs out of the area so there are no nearby trees for the beetles to migrate towards.

Since we have neighbors living on the prairie who need firewood the solution is obvious to us. Our church has split and delivered large amounts of firewood. Last year we delivered over 40 cords.

The logs keep coming in.

The logs keep coming in.

This week we are planning a caravan to haul unsplit logs to our partners on the Cheyenne River Reservation north of Eagle Butte. We need to get the bug logs out of the forest and they will need the firewood next year. Sometime in the summer, we will meet up with our reservation partners for a splitting party to split and stack the wood on the reservation. We will get to know the people of the reservation churches better and deepen our relationships as well as provide energy for warmth in the winter. It is a win-win situation.

Our winter was unseasonably mild and spring seems to be following in the same pattern. That is not the best news for the trees. A harsher winter and more moisture would help the trees survive the beetle attacks better. More snow and rainfall would decrease the fire danger as well. But we don’t control the weather.

It looks like we have plenty of logs to split and firewood to deliver for a long time to come.

I spent an additional ten years of my life in Boise, Idaho. The story of that town’s name dates back to the days of French Fur trappers who were said to have uttered upon discovering the area, “Les Bois!, Lest Bois!” Actually the trees in Boise aren’t all that spectacular. It seems that the fur trappers had been wandering in the desert for several days and so just finding a place with some trees was an exciting discovery.

Still, I have had a deep appreciation for trees all of my life. All of my growing up summers included time at our Church Camp, Mimanagish, high up the boulder valley nestled in huge stands of lodgepole pine. There really is something very wonderful about the whisper of the wind in the pine trees. I assumed that I would always live in a place where there was an ample supply of trees.

Graduating from seminary, however, we found ourselves called to rural North Dakota. I had a fairly large collection of North Dakota jokes and some biases about life on the prairie. I had tried to find a call in a mountainous location, but God has a wonderful sense of humor and we headed across the prairie to our new home. My biases turned out to be wrong. It was a wonderful place to live. I grew to enjoy the open space, the ability to see long distances, the view from the top of a small hill or rise, and especially the people who lived there. To be honest, our town was not without trees. There just weren’t very many of them outside of town.

We hate to lose any tree. Losing thousands is no picnic.

One of the ways to slow the spread of the beetles is to remove the affected trees. Many landowners have been aggressive about felling trees lost to the beetles. The trees are then cut into short lengths and left scattered in the forest. Another technique is to cover the loges with plastic to contain the insects and raise temperature levels. An even better technique is to haul the logs out of the area so there are no nearby trees for the beetles to migrate towards.

Since we have neighbors living on the prairie who need firewood the solution is obvious to us. Our church has split and delivered large amounts of firewood. Last year we delivered over 40 cords.

This week we are planning a caravan to haul unsplit logs to our partners on the Cheyenne River Reservation north of Eagle Butte. We need to get the bug logs out of the forest and they will need the firewood next year. Sometime in the summer, we will meet up with our reservation partners for a splitting party to split and stack the wood on the reservation. We will get to know the people of the reservation churches better and deepen our relationships as well as provide energy for warmth in the winter. It is a win-win situation.

Our winter was unseasonably mild and spring seems to be following in the same pattern. That is not the best news for the trees. A harsher winter and more moisture would help the trees survive the beetle attacks better. More snow and rainfall would decrease the fire danger as well. But we don’t control the weather.

It looks like we have plenty of logs to split and firewood to deliver for a long time to come.