The Reign of Christ

25/11/12 05:06

Today is the last Sunday of the Christian Calendar. We start a new year with the First Sunday of Advent next Sunday. The traditional name for the last Sunday of the Christian year is “Christ the King” Sunday. After the longest season of the year and weeks of reading about the life and ministry of Jesus, we skip over the stories of his crucifixion, which are saved for Lent, and celebrate the reign of Christ over all of the world. In fact, many communions of Christians use the name “Reign of Christ” in place of “Christ the King” as the name of the day.

The celebration presents some unique theological challenges. But first a bit of background is in order. Christianity began its journey under the domination of the Roman Empire. It eventually became mainstream within the empire, but in its early years it was considered to be an illegal religion and practitioners of that faith were persecuted and executed for their beliefs. Jesus himself was very countercultural and his crucifixion was done under the authority of the Roman government. In the face of this persecution, the early church began to formulate a simple theological declaration. Kings are not gods. The one true God is not embodied by the authority of human governments. There was a parallel construction that is even more challenging for contemporary Christians: patriotism is not the same thing as faith. Loyalty to a human government is different from obeying the commandment to love God with all of one’s heart, soul, mind and strength. When forced to choose between government and God, the Christian was called to respond to a higher authority.

In the early days, there was no shortage of martyrs. John, from the context of exile on the island of Patmos, was worried about the power of the Roman government to cause suffering and persecution of Christians. It was there that he wrote down his revelation that has become the final book of the Christian New Testament. Like all visions, it is clear that John was trying to describe something that is clearly beyond words. The use of symbolic language and metaphor is an evident attempt to say more than mere words can convey. The problem with this kind of language is that it is not only subject to interpretation by contemporary readers, it is prone to misinterpretation. There is no shortage of Christians who read into the text current events and personalities that could not possibly have had any relevance to the book’s author or generations of its readers.

In the early days, there was no shortage of martyrs. John, from the context of exile on the island of Patmos, was worried about the power of the Roman government to cause suffering and persecution of Christians. It was there that he wrote down his revelation that has become the final book of the Christian New Testament. Like all visions, it is clear that John was trying to describe something that is clearly beyond words. The use of symbolic language and metaphor is an evident attempt to say more than mere words can convey. The problem with this kind of language is that it is not only subject to interpretation by contemporary readers, it is prone to misinterpretation. There is no shortage of Christians who read into the text current events and personalities that could not possibly have had any relevance to the book’s author or generations of its readers.

But we are always handed texts from the Revelation of John for this Sunday. And it is a pastor’s obligation to attempt to make connections between the sacred texts and the everyday lives of the members of the congregations that we serve.

It is a perilous task, in my opinion. Jesus of Nazareth throughout his life before his crucifixion was not the king of messiah that many expected. He did not foment revolution against Roman authority. He didn’t play power politics. He didn’t advocate rule by strength or fear or intimidation. He seemed little concerned with taxation and other functions of government. He told his followers that whoever wants to be greatest must be the least of all and the servant of all. Then he demonstrated his words with a life of service, including washing the feet of his disciples. To equate the kind of leadership Jesus revealed with the way human governments work is a fallacy. But the language we have to speak of Christ is the language of humans.

In the English language, this is exacerbated by the fact that English translations of scriptures came about under the authority of a monarchy. The King James Version of the Bible uses the language of the English monarchy to speak of the authority of heaven. The four Hebrew letters of God’s name are consistently translated “Lord” by the KJV. The very name “Christ the King” uses the title of the English monarch.

The Congregational Church, forged in the time of the American Revolution from England, didn’t practice anything “the king.” Christ the King Sunday was not a part of the traditions of our corner of the church until it was recovered in relatively recent decades by those wanting to made a deeper connection to historic liturgy and the spiritual practices of the wider church.

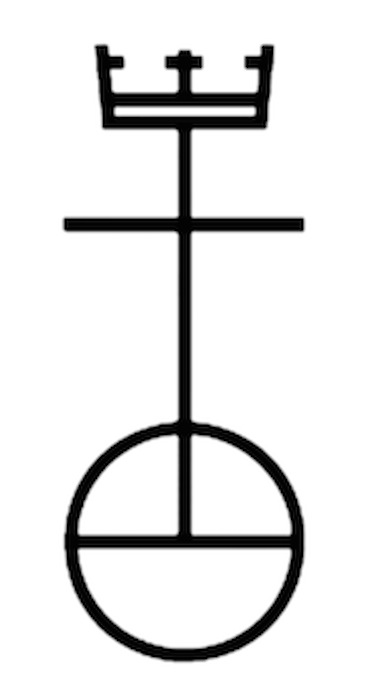

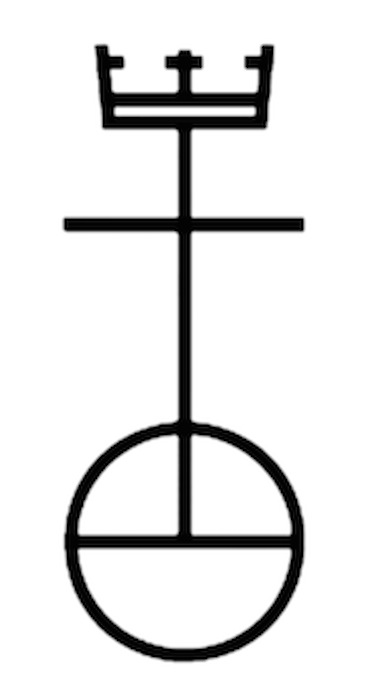

So we celebrate uncomfortably. We know that the use of royal language fails to speak of the different way in which God’s realm works. We know that declaring that Jesus is king over all of the earth risks forgetting the call to service and the basic humility of Jesus way of interacting with others. Yet the symbol of our denomination is the Cross of Christ on top of the globe, itself topped with a crown. We declare that in moments of conflict between God’s authority and the authority of worldly leaders God’s way always triumphs, even when it seems at the time that earthly powers prevail.

So we celebrate uncomfortably. We know that the use of royal language fails to speak of the different way in which God’s realm works. We know that declaring that Jesus is king over all of the earth risks forgetting the call to service and the basic humility of Jesus way of interacting with others. Yet the symbol of our denomination is the Cross of Christ on top of the globe, itself topped with a crown. We declare that in moments of conflict between God’s authority and the authority of worldly leaders God’s way always triumphs, even when it seems at the time that earthly powers prevail.

Today, as has been the case for many years, I include in my preparations for the task of preaching a poem. I’ll conclude this blog with its thoughts.

"God's True Cloak" by Rainer Maria Rilke

translation by Joanna Macy + Anita Barrows

We must not portray you in king's robes, you drifting mist that brought forth the morning.

Once again from the old paintboxes we take the same gold for scepter and crown that has disguised you through the ages.

Piously we produce our images of you till they stand around you like a thousand walls. And when our hearts would simply open, our fervant hands hide you.

Book of Hours, I 4

The celebration presents some unique theological challenges. But first a bit of background is in order. Christianity began its journey under the domination of the Roman Empire. It eventually became mainstream within the empire, but in its early years it was considered to be an illegal religion and practitioners of that faith were persecuted and executed for their beliefs. Jesus himself was very countercultural and his crucifixion was done under the authority of the Roman government. In the face of this persecution, the early church began to formulate a simple theological declaration. Kings are not gods. The one true God is not embodied by the authority of human governments. There was a parallel construction that is even more challenging for contemporary Christians: patriotism is not the same thing as faith. Loyalty to a human government is different from obeying the commandment to love God with all of one’s heart, soul, mind and strength. When forced to choose between government and God, the Christian was called to respond to a higher authority.

But we are always handed texts from the Revelation of John for this Sunday. And it is a pastor’s obligation to attempt to make connections between the sacred texts and the everyday lives of the members of the congregations that we serve.

It is a perilous task, in my opinion. Jesus of Nazareth throughout his life before his crucifixion was not the king of messiah that many expected. He did not foment revolution against Roman authority. He didn’t play power politics. He didn’t advocate rule by strength or fear or intimidation. He seemed little concerned with taxation and other functions of government. He told his followers that whoever wants to be greatest must be the least of all and the servant of all. Then he demonstrated his words with a life of service, including washing the feet of his disciples. To equate the kind of leadership Jesus revealed with the way human governments work is a fallacy. But the language we have to speak of Christ is the language of humans.

In the English language, this is exacerbated by the fact that English translations of scriptures came about under the authority of a monarchy. The King James Version of the Bible uses the language of the English monarchy to speak of the authority of heaven. The four Hebrew letters of God’s name are consistently translated “Lord” by the KJV. The very name “Christ the King” uses the title of the English monarch.

The Congregational Church, forged in the time of the American Revolution from England, didn’t practice anything “the king.” Christ the King Sunday was not a part of the traditions of our corner of the church until it was recovered in relatively recent decades by those wanting to made a deeper connection to historic liturgy and the spiritual practices of the wider church.

Today, as has been the case for many years, I include in my preparations for the task of preaching a poem. I’ll conclude this blog with its thoughts.

"God's True Cloak" by Rainer Maria Rilke

translation by Joanna Macy + Anita Barrows

We must not portray you in king's robes, you drifting mist that brought forth the morning.

Once again from the old paintboxes we take the same gold for scepter and crown that has disguised you through the ages.

Piously we produce our images of you till they stand around you like a thousand walls. And when our hearts would simply open, our fervant hands hide you.

Book of Hours, I 4